The benefits of exercise for people living with and beyond a cancer diagnosis are well established. A wide range of types and intensities of exercise have been shown to improve quality of life, reduce anxiety and depression, reduce cancer-related fatigue, improve treatment tolerance, and potentially lead to extended life.

The compelling evidence demonstrating the benefits of exercise for cancer survivors led to both the Exercise and Sports Science Australia (ESSA) and the Clinical Oncology Society of Australia (COSA) to call for exercise therapy to be embedded as standardised care for people with cancer.

“Exercise is widely accepted as safe, even for people living with or beyond cancer,” said Dr Rosa Spence, Research Fellow and senior member of ihop.

“However, every healthcare intervention brings risk of harm alongside potential for benefit. Unlike benefits, the harms of exercise have been poorly reported in exercise oncology trials to date, with the majority of studies failing to report or under-reporting harms.

“The problem with this is that widespread uptake of exercise into standard cancer care will require evidence of both benefit and low risk of harm across all cancer and treatment types and at the moment there is an evidence gap.

“There has been growing recognition across clinical trial disciplines of the need to provide balanced reporting of benefits and harms.

“This is why we designed the Exercise Harms Reporting Method or ExHarM protocol,” she said.

“This protocol is specifically designed for harms assessment within exercise oncology trials but can also be applicable in other behaviour change settings.”

Dr Spence says she defines the harms of exercise as ‘all undesirable, physical, psychological, economic or social consequences that are related to an individual’s participation in exercise’.

“It’s important for clinicians, patients and exercise professionals to understand the potential harms of exercise to ensure exercise is recommended to the right patients, prescribed in the right way and that individuals can make informed decisions about the potential positives and negatives of exercise participation ,” she said.

“The ExHarm protocol was developed, trialled and refined by the ihop research group to guide comprehensive and reliable harms assessment and reporting in both research and in practice.

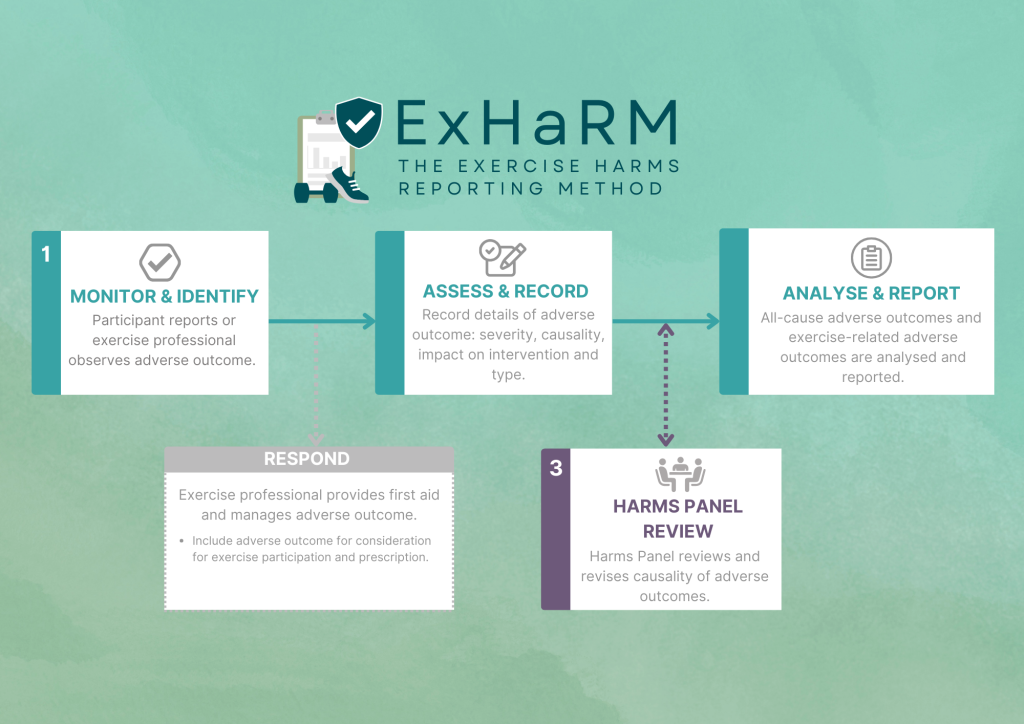

“The protocol involves four core steps to capture, classify, analyse and report all adverse outcomes relating to exercise therapy,” she said.

- Step 1 – Monitor and Identify – the participant reports or exercise professional observes adverse outcome.

- Step 2 – Assess and record – record details of adverse outcome, severity, causality, impact on intervention and type of adverse outcome.

- Step 3 – Harms panel review – harms panel reviews and revises causality of adverse outcomes.

- Step 4 – Analyse and report – all-cause adverse outcomes and exercise-related adverse outcomes are analysed and reported.

Dr Spence says the four-step process provides a simple framework for the collection, classification, analysis and reporting of adverse outcomes.

“ExHarm was developed with the goal of improving the quality of harms assessment and reporting within exercise oncology research and practice,” she said.

“It has been successfully implemented in multiple exercise oncology trials, involving samples with different cancer types (breast, brain and gynaecological), different stages of disease at diagnosis (stage I-IV), primary and recurrent diagnoses, and inclusion of samples with multiple comorbidities.

“Our hope is to continue to refine the protocol and continue to work to improve harms reporting across exercise research, with the goal of improving the quality of life for people living with and beyond cancer.”

To read the full manuscript on ExHaRM visit

ExHaRM Manuscript (BMJ Open)

For more information about the ihop research group, visit improvinghealth.com.au